Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufinus). Photo R. Al Hajii.

The main focus of our tracking effort thus far has been on Greater Spotted Eagles (Clanga clanga), however we have tracked other species, including Long-legged Buzzards (Buteo rufinus). We blogged about our tracking of them here. The story of one of the tracked Long-legged Buzzards sheds light on a conservation issue that many birds are facing: removal of birds from the wild population via killing or live capture.

Tracking by ourselves and others supports evidence from other sources that many migratory birds are being captured or killed on migration or on their wintering grounds. The reasons for capturing and killing birds are varied. Some of the birds turn up in markets or on the internet for sale, and some, especially large falcons, are supplied directly to buyers in other countries. Other birds, particularly Marsh Warbler (Acrocephalus palustris) are being captured and killed for food — they seem to be a special delicacy in the Al Mahrah Governorate of Yemen (Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Marsh Warblers (Acrocephalus palustris) being caught for food in Al Mahrah Governorate, Yemen (Photo by Ahmed Suleiman Abdullah).

Figure 2. Marsh Warblers (Acrocephalus palustris) prepared for human consumption in Al Mahrah Governorate, Yemen (Photo by Ahmed Suleiman Abdullah).

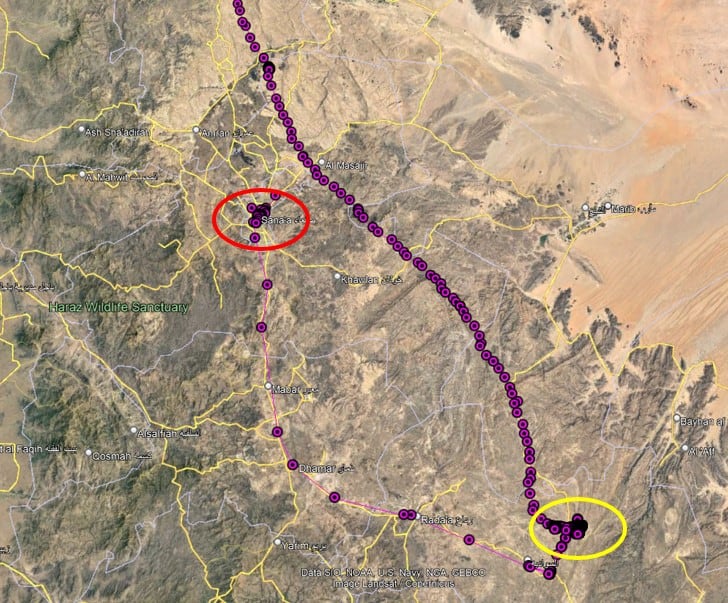

We captured a Long-legged Buzzard (8696) at Al Jahra Reserve on March 22 2023. We tracked it for over 7 months, until early January 2023. See Fig. 3 below. During that time it migrated north and spent its summer in western Iran and Armenia. Movements suggested that the bird did not breed. Look back at this earlier blog post. In autumn 2022 it migrated south to Yemen. In Yemen tracking indicated that it was captured. probably around 18 December, and taken to the capital city of Sanaa (Figure 4). We alerted colleagues in Yemen, who were able to say that the bird or the transmitter or both were in the hands of the security forces. Our colleagues spent some time trying to find out more about the fate of that bird, but with no luck.

Figure 3. Movements of a Long-legged Buzzard (8696) from Kuwait in March 2022 to Armenia in summer 2022, and then south to Yemen during winter 2022–23.

Figure 4. Movements of a Long-legged Buzzard during winter 2022–23 in Yemen. The yellow circle covers the period 13-18 December, and is where the bird/tag was captured. The tag was then transported by road to the capital, Sanaa, where locations were received during 22 December 2022 – 3 January 2023.

This story highlights a number of things…

First: Long-legged Buzzards are a migratory species that visit Kuwait in the winter, but also winter in other parts of Arabia. This, of course, is what occurs naturally as part of this species’ annual cycle. However and as a consequence, this means that for part of the year the responsibility of conserving these and other species falls to the countries where they winter, including the countries of Arabia.

Second: A wide-range of migratory birds are illegally captured on their wintering grounds. Some, like the Marsh Warblers, are traditionally caught for food in the Al Mahra Governorate of Yemen. See photos below. Raptors are caught and sold for falconry, as lures for capturing falcons, and as curiosities. See photo below. In Yemen poverty and war are the underlying reasons for much of the illegal capture, and the inability of the environmental authorities to enforce laws.

It is not known whether the Long-legged Buzzard we were tracking was captured and sold. If it was, then it was probably not for falconry because it is not a species favoured for falconry. More likely is that those who captured the bird just wanted to sell it for whatever amount they could get, or they may have just contacted the security forces out of caution. The laws about wildlife capture and trade vary between countries, as does the enforcement of any laws. Enforcing environmental laws in Yemen is made extraordinarily difficult due to the war, including the fact that some areas are under the control of non-government forces.

Figure 5. A Steppe Eagle on sale at a market in Yemen in 2023 (Photo by Ahmed Suleiman Abdullah).

Third: Improvements in tracking technology and lower costs have meant that many more birds of many more species are being tracked. Indeed, those factors contributed to our own ability to conduct our tracking study. Tracked birds are often viewed by security forces (or insecurity forces) as suspicious, and possibly as a means of spying. Of course these suspicions are heightened when there is conflict or tensions between countries, tribes, groups. One needs not be reminded that there have been “tensions” in Yemen for some time now, and there are a few cases of which we are aware of birds being tracked from Israel ending up in the hands of police and security forces in Sudan and Saudi Arabia, and newspaper accounts suggesting that the birds were “spies” (Click هنا).

It has long been known that migratory birds are being captured and killed. For some (but definitely not all) species, some loss from such activities might be sustainable, if managed (i.e. sustainable hunting). However, there is little evidence that sustainable removal of birds has been (is being) practiced in many parts of the world, including Arabia. Recent changes in laws and increased enforcement of those laws in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia are moving in the right direction, but much, much more needs to be done.